|

My department should reform its undergraduate curriculum. I've been thinking about this for a while, and some may recall that this was a priority when I ran for chair. This isn't about improving teaching. We're a pretty phenomenal teaching department. It's about looking at the big picture and considering whether and how programatic changes would help our students transition after graduation.

The current curriculum is pretty standard. Students must complete 30 hours. Among those hours, students must complete:

2 Comments

As editor of the journal Politics and Religion, I routinely get inquiries from authors wanting to know the status of their manuscript. That's no problem. I'm happy to provide updates.

In the last week, however, several authors have written to ask why their manuscripts still appears as "With Editor" and not "Under Review" in Editorial Manager. One author even withdrew their manuscript, because they thought we were taking too long. In light of that, I thought it would be helpful to explain what happens when you submit your piece to Politics and Religion (PAR). We don't immediately send manuscripts out for review. Here's what happens.  My department just had a chair election. I wasn't going to run. I'd thought about it, but the timing didn't seem great for a variety of non-work-related reasons. To my surprise, however, someone nominated me. I decided to stay in the race because I have aspirations for the department, and I thought I'd be in a better position to pursue those as chair. Running for chair means putting yourself out there, and that's not like me. My imposter syndrome is at its peak around my departmental colleagues -- so much so that in my 16.5 years at UNT I have not so much as given a research brownbag presentation. I'm a tenured full professor and editor-in-chief of a key field journal, but it's still not too late for my colleagues to realize their mistake in hiring me! Anyway, I was determined to Brené Brown the shit out of my presentation to the department. I took some deep breaths, 5 mg of Clonazepam, and did my thing. There was clapping and nodding. I thought it went well. I thought it went great, if I'm being honest. Last week, Michael Greig and I wrote a post on President Trump’s decision to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. Several days later I had a conversation with Vox’s Sean Illing as to why Jerusalem is so important to evangelical Protestants. Here’s the short version.

Christian theology includes several schools of thought on the end times. Among these, premillennial dispensationalism provides key teachings on the Jewish people and, by extension, the status of Jerusalem. Adherents to this particular flavor of eschatology believe that God’s biblical promise of the Holy Land to the Jewish people is literal and eternal. When the second coming occurs, there will be a tribulation marked by war and natural disaster, during which Christ will defeat evil, and the Jewish people will accept Christ as the Messiah. This will be followed by a Millennium—a gold age during which Christ will .... Read the remainder at Religioninpublic.blog. By J. Michael Greig and Elizabeth Oldmixon

President Trump recently recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. This is consistent with U.S. policy set by the Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995, which states that “Jerusalem should be recognized as the capital of the State of Israel.” Even so, the law allows presidents to waive the requirement to move the U.S. Embassy in order “to protect the national security interests of the United States.” Every president since Clinton—including Trump—has issued waivers. Why? Because Jerusalem is a sacred place for Christians, Jews, and Muslims alike. As such, asserting Israeli sovereignty is likely to enflame .... Read the remainder of the post at Religioninpublic.blog. Last year, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick garnered national headlines when he started taking a knee during the national anthem in protest of police violence and racial oppression. He was joined by a handful of other professional athletes, including Megan Rapinoe and Eric Reid. Kaepernick became a free agent at the end of the season. He remains unsigned, and the NFL has had to contend with allegations that he ....

Read the remainder of the post at Religioninpublic.blog. Crux recently reported an uptick in suicides among Catholic priests in Ireland. “At least eight priests in Ireland have committed suicide in the past 10 years,” and there is growing concern for priests’ morale and mental health as they grapple with a drop in vocations, the sexual abuse scandal(s) that came to light in the 1990s, and a drop in religious practice among the Irish people. As Tom Inglis argues, the Catholic Church maintained a “moral monopoly” over Irish society and politics for many years. As the monopoly slowly erodes, the effects redound to clergy in the form of ....

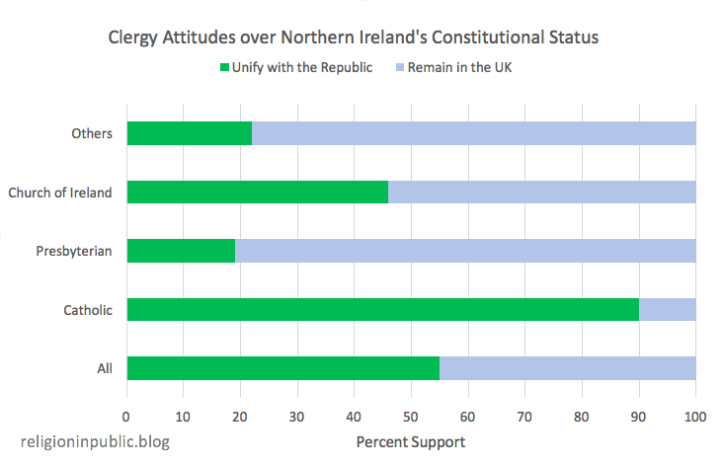

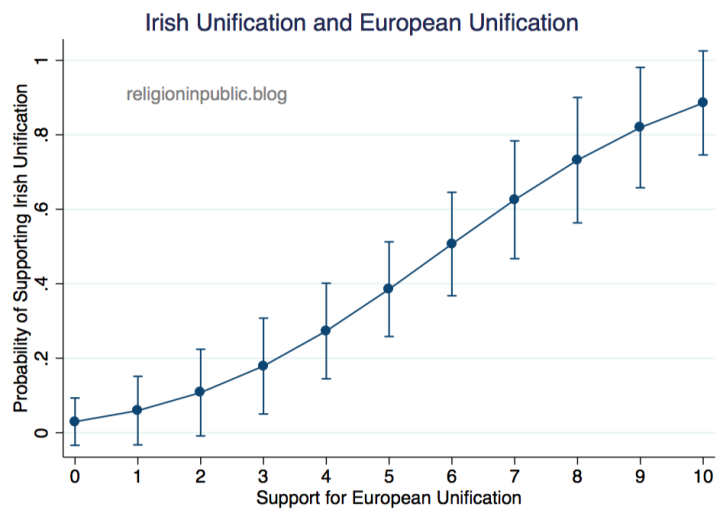

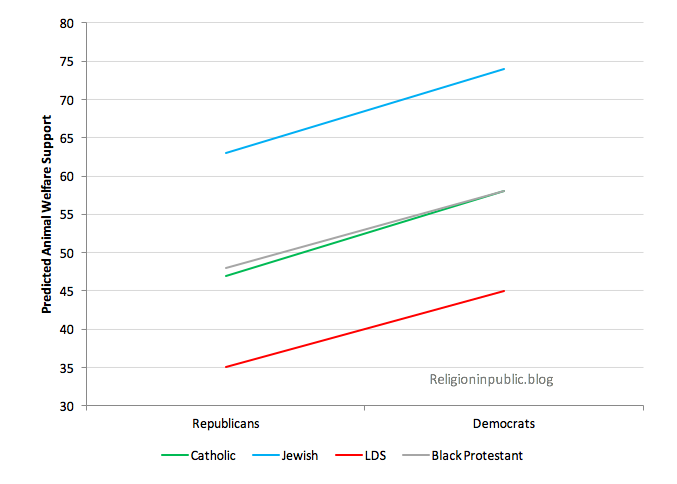

Read the remainder of the post at Religioninpublic.blog.  Crossposted from Religioninpublic.blog. Elizabeth Oldmixon, University of North Texas Photo credit: me [1] On February 3, 2017, the United States Department of Agriculture released a statement indicating that animal welfare data collected in relation to the Animal Welfare Act and Horse Protection Act would no longer be publicly available. In the future, interested parties will need to make a FOIA request to access the information. With that, the agency “removed inspection reports and other information from its website about the treatment of animals at thousands of research laboratories, zoos, dog breeding operations and other facilities.” PETA condemned the move, but as the Washington Post reports, certain business interests clearly benefit from the diminished regulatory burden. The business versus animal activist cleavage is about what you would expect here, but there is also a religious dimension to animal welfare policymaking, which I investigate in a forthcoming article in Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. Religionists who study legislative policymaking often focus on so-called culture war issues such as school prayer, LGBTQ rights, and reproductive policy (but see exceptions related to economic policy, human rights, and foreign policy). This is in part because culture war issues were championed by white evangelicals at the time of their “wholly unexpected … political resurgence … in the late 1970s.” Religionists consistently find that religious identities and constituencies structure legislative behavior. These are important and interesting findings.[2] But given their salience—given the priority evangelicals gave these issues when they joined the Republican Party—culture war issues have well-worn partisan and religious frames. We know, however, that religious politics extends beyond evangelical politics, and evangelical politics extends beyond the culture wars. Indeed, the social connections and beliefs associated with religion provide the faithful with a fairly comprehensive worldview. Assuming that legislators bring their personal values to bear on the policy process, the imprint of religion should be observable well beyond the usual suspects. The challenge for religionists, then, is to investigate lower salience issues, so as to develop a more complete picture of religious thinking and politics. A finding that religion affects legislative behavior on issues that lack entrenched partisan and religious frames would suggest that religion’s influence is more widely diffused than the scholarly community generally recognizes. The crux of the theoretical argument is that legislators bring their personal religious values to bear on policy decisions. Kingdon characterizes legislative voting as a sequential process wherein legislators weigh environmental cues. Under the right circumstances—when the issue is low salience, when policy goals are implicated, when a president of the same party is indifferent—legislators can vote in accordance with their policy goals. Legislators can engage in what Barry Burden calls “personal representation,” acting on their personal religious values, while balancing external influences, such as political and economic factors. Animal welfare is just such a low salience issue. The Catholic Church and the Southern Baptist Convention have both issued documents on animal welfare, but it is nowhere near the top of the political agenda.[3]  In order to suss this out, I analyzed Humane Society Legislative Fund (HSLF) animal welfare scores for U.S. senators from the 109th to the 113th Congress (2005-2014).[4]Scores reflect percent support for the HSLF’s legislative agenda. Over the 10-year period considered in the analysis, mean animal welfare scores fluctuated between 35% and 51%. The figure above provides the predicted level of animal welfare support by a senator’s religion and party. Across religious groups, Democratic support is higher than Republican support. Predictable and consistent religious differences also emerge. Among Republicans and Democrats alike, LDS Senators are the least supportive of animal welfare, while Jewish senators are the most supportive. Catholic and Black Protestant support is in the middle and nearly identical.[5] Senators represent religious constituencies, too. I find that when taking religious constituencies into consideration, as the Black Protestant share of the population increases, so too does the level of senatorial support for animal welfare. As Evangelical and Mainline Protestant shares of the population increase, senatorial animal welfare support decreases. The figure below depicts these relationships, providing predicted values of animal welfare support different given religious population levels.  Cross-posted from Religioninpublic.blog. Elizabeth A. Oldmixon, University of North Texas Photo credit: me Clergy face high barriers to political engagement in Ireland. Like their American peers, they tend to have many of the characteristics associated with potent political activism, and they lead communities where people seek moral guidance and learn civic skills. Owing to Reformation politics, colonialism, and a history of oppressions, however, religious identities overlap considerably with national identities. Roman Catholicism emerged as the lodestar of Irish nationalism, and Protestantism became a symbol of British identity. This makes prophetic engagement across religious communities difficult. Adding to this, Britain partitioned the six counties of Ulster from the rest of Ireland in 1920; the southern counties would eventually form an independent sovereign state, the Republic of Ireland, while the northern counties became Northern Ireland, a constituent member of the United Kingdom. Catholics comprised (and comprise) a substantial numerical majority in the Republic, and this allowed the Church to establish what Tom Inglis calls a “moral monopoly.” Priests did not need to engage politics because the very terms of political discourse were set by the Catholic Church. In Northern Ireland, by contrast, Catholics were and are numerically disadvantaged. As such, the Church never developed the sociocultural pre-eminence that it enjoyed in the south. Catholic priests were involved in republican politics, but by the 1970s many were skeptical of their actual influence and reluctant to engage. Adding to this, the need for engagement may have been mitigated by the mapping of religious identities onto the party system – someone was already carrying water for the Church. The June 23, 2016, Brexit vote may disrupt the political milieu in the North, raising the possibility in some circles of a united Ireland, and drawing clergy into the public square. Why? While a slim majority of UK citizens voted to leave the European Union, nearly 56% of voters in Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU. The Republic of Ireland has no plans to leave the EU, so in the wake of the vote, “Protestant unionists are queuing for Irish passports in Belfast and once quiet Catholic nationalists are openly campaigning for a united Ireland.” Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin went so far as to suggest that, “The remain vote may show people the need to rethink current arrangements. I hope it moves us towards majority support for unification, and if it does we should trigger a reunification referendum.”  For many in Northern Ireland and the Republic, EU membership is associated not only with economic modernization and stability, but also peace and security. Under the auspices of EU membership, free movement across the border has become the norm, and both countries enjoy greater cooperation with respect to trade and healthcare. This was codified by the Good Friday Agreements, which Gerry Adams argues were “founded on the democratic principle that the people of Ireland, North and South, should determine their own future.” Brexit threatens to undo all that, imposing a hard border, inflicting financial costs, and threatening to disrupt the peace in Northern Ireland. The disruption may already be underway. The Independent reports that in order to secure the necessary votes in Parliament for her Brexit plan, Prime Minister Theresa May has had to make concessions to DUP (Democratic Unionist Party) MPs. Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland Martin McGuinness, pictured to the left, recently resigned his position, effectively ending the power-sharing agreement established by the Good Friday Agreements. McGuinness resigned in protest over alleged financial impropriety by a DUP legislator, but the larger concern is that May refuses to reign in DUP given that she needs their votes. What role might clergy play in these developments? The “remain” vote crosscut communities, creating the possibility of coalition building on the future of Northern Ireland’s constitutional status. Leadership opportunities for clergy emerge as the faithful sort themselves on this issue. It is interesting to consider, then, clergy attitudes on the question of Irish unification. To the best of my knowledge, there are no post-Brexit clergy survey data on this issue. However, Brian Calfano and I have published a series of articles and a book on clergy in Ireland (here and here with Jane Suiter, and here with Melissa Michelson). The 2011 iteration of our original survey included a question on clergy preferences for the long-term future of Northern Ireland. The results are provided in the figure below.[1] Though we have only 67 observations, it is clear that Catholic clergy prefer unification by an overwhelming majority, while Protestant and other clergy prefer to remain in the UK. Regressing preferences for Northern Ireland’s future on clergy religious identification, and using the other, smaller traditions as the reference category, the relationships do not achieve significance. When controlling for general attitudes toward unification with Europe[2], however, interesting results emerge. Presbyterians are indistinguishable from the smaller denominations, while Catholic and COI (Church of Ireland) clergy are both strongly supportive of Irish unification. Indeed, their probability of supporting unification is more than twice that of their peers. The probability of Catholic clergy supporting unification is .58, as compared to .23 for their peers; the probability of COI clergy supporting unification is .70, as compared to .31 for their peers. Two findings merit further comment. First, the COI finding is surprising at first glance. A member of the Anglican Communion, the COI was effectively the establishment church in Ireland for over 300 years. Catholic churches were confiscated by the state on its behalf, and it was aided by the Penal Laws, which oppressed Catholics and Protestant dissenters who would not assent to membership. Surely these Anglicans would feel a close connection to Britain. The Church of Ireland, however, has always been an all-island church and claims a succession of bishops back to St. Patrick, whereas Presbyterianism has deep ties to Ulster specifically. Scottish Presbyterians were settled in Ulster by the British in the 17th century to establish a Protestant outpost. In the aggregate, then, COI clergy have weaker ties to British unionism than their Protestant peers. Our data indicate that a higher proportion of COI than Presbyterian clergy identify as Irish—as opposed to UK—nationals (46% and 19%, respectively), and COI clergy are less likely than Presbyterian clergy to support unionist political parties such as DUP. Second, as the figure above demonstrates, clergy preferences over Northern Ireland’s constitutional status are strongly linked with attitudes toward Northern Ireland’s place in Europe. As support for European unification goes up, so too does the probability of support for Irish unification. The default view looking at politics in Northern Ireland is to reduce political conflict to community conflict, and of course that is present, but there is also a clear globalist subtext. Supporters of Irish unification prefer deeper connections to Europe, not simply (or even necessarily) a unified Ireland for its own sake. This may be more about a widely diffuse preference for soft borders and cross-border cooperation, which is part and parcel of European unification, than anything else.

If the Brexit vote in Northern Ireland was about Europeanization, then the people of Northern Ireland—Protestants and Catholics alike—are drawn into closer alignment with the Republic. This does not mean that a change in Northern Ireland’s constitutional status is in the offing. But it does mean that Northern Ireland’s political context has changed with the development of a new, cross-cutting alignment. As the people of Northern Ireland grapple with Brexit’s aftereffects, the politics are unsettled. This creates space for clergy to enter a political breach less steeped in ethno-religious nationalism. Elizabeth A. Oldmixon is associate professor of political science at the University of North Texas and editor-in-chief of Politics and Religion. She can be contacted via Twitter. Further information, including the data used in this analysis, can be found on her personal website. Notes [1] Question wording: “In terms of the long-term future of Northern Ireland, which would you prefer? Northern Ireland should: a) remain in the UK and have a strong Assembly and government in Northern Ireland; b) remain in the UK with a direct and strong link to Britain; c) unify with the Republic of Ireland.” The two remain response options were collapse for ease of analysis. [2] Question wording: European Unification Scale: 0 = European unification has already gone too far to 10 = European unification should be pushed further Share this: Mehmet Gurses, Nicholas Tampio, and myself are excited to start our editorial term at Politics and Religion, and we thank the APSA's Religion and Politics Section for entrusting us with this responsibility. Over the next few days, the journal’s Cambridge homepage will reflect several new developments. We would like to bring a few of these to your attention.

First, you can reach us at PandRJournal@unt.edu. Second, in addition to articles, Politics and Religion will now accept notes. These are meant to be problem-driven research manuscripts that address timely political issues, replicate existing research, and/or report null findings. Notes should be about 4,500 words in length, including notes and references, but not tables and figures. Third, we have opted not to sign the JETS statement on Data Access & Research Transparency (DA-RT) at this time. This is something we will continue to weigh moving forward. We have, however, adopted the following policy in this area: “The Editors affirm the importance of data transparency in evidence-based political science research. Authors are required to clearly specify their analytical techniques and outside sources of funding and encouraged to make their data publically available at the time of publication. The Editors understand, however, that the latter may not be possible or ethical, to the degree that data are proprietary, sensitive, or newly collected. Authors using publically available data should provide a DOI citation where possible.” Fourth, the journal has a new Editorial Board. We are delighted and grateful that these fine scholars agreed to serve. They are as follows. Bethany Albertson, University of Texas at Austin, USA Victor Asal, University at Albany, SUNY, USA Tongdong Bai, Fudan University, Shanghai, China David Bosworth, Catholic University of America, USA R. Khari Brown, Wayne State University, USA David Campbell, University of Notre Dame, USA Jocelyne Cesari, University of Birmingham, UK Michael Correa-Jones, University of Pennsylvania, USA Daniel Dreisbach, American University, USA Michael D. Driessen, John Cabot University, Italy Amanda Friesen, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, USA Farah Godrej, University of California-Riverside, USA Cengiz Gunes, The Open University, UK Ekrem Karakoc, Binghamton University, SUNY, USA Katherine Knutson, Gustavus Adolphus College, USA Karrie J. Koesel, University of Notre Dame, USA Geoffrey C. Layman, University of Notre Dame, USA Andrew F. March, Yale University, USA Ani Sarkissian, Michigan State University, USA Amy Erica Smith, Iowa State University, USA Anand Edward Sokhey, University of Colorado, Boulder, USA Lavinia Stan, St. Francis Xavier University, Canada Isak Svensson, Uppsala University, Sweden Sultan Tepe, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Lars Tønder, University of Copenhagen, Denmark Finally, we thank Angie Wilson and Paul Djupe for their service as editors. We will try to live up to the high bar they set over the last five years—no easy task! Best wishes for the New Year, Elizabeth Elizabeth A. Oldmixon, Editor-in-Chief Mehmet Gurses and Nicholas Tampio, Editors Politics and Religion |